In this digital age, where words can reverberate more powerfully than actions, understanding the discourse that shapes our perception is more important than ever. Howarth provides a lens through which we can examine the communication web that constructs our social reality in his¬†work on “Discourse” (Howarth, 2000), with a focus on the dynamic social media landscape.

“Covering Islam” (Said, 1997) is a compelling example of discourse in action. His investigation into how Islam is reported in the media, particularly in the context of news as a form of discourse, reveals the layers of meaning that influence public perception. Said’s analysis demonstrates how repeated themes and framing not only inform but also shape opinions, resulting in a ‘Us versus Them’ narrative that pervades public consciousness (Said, 1997, Chapter One).

Similarly, Policy Options described how the framing of the Syrian refugee crisis in Canadian media changed over time, reflecting a shift in discourse from security concerns to human stories, influencing public sentiment (Wallace, 2018). The Black Lives Matter movement changed the way people talked about race, according to the University of Washington News, demonstrating the tangible impact of social media-driven discourse on public awareness (Eckart, 2022).

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance of media framing. A Routledge publication investigates how media narratives shaped public discourse during the health crisis, reflecting the power dynamics in the media landscape (Price and Harbisher, 2021). A study published in the journal PLOS ONE reveals how metaphorical framing on Twitter influenced perceptions of the pandemic, highlighting the platform’s role in conceptualising a global health emergency (Wicke and Bolognesi, 2020).

The PLOS ONE (Wicke and Bolognesi, 2020) study delves into the world of Twitter and how it frames the COVID-19 discussion. It’s not just random tweets. The language we use, whether it’s war metaphors or journey analogies, not only reflects but actively shapes our emotions. Consider this: if we talk about the pandemic as a war, it may rally us to support strict policies because we’re in “battle mode.” However, if it is framed as a journey, it may evoke a sense of togetherness, reminding us that we are all in this for the long haul.

Now, let’s talk about Price and Harbisher’s book (2021). It’s eye-opening to see how media giants can steer the pandemic narrative. It’s not always about the truth, but what they want us to believe or feel. This manipulation can cause fear if the story is bleak, or resilience if the story is upbeat. The media controls the joystick in this game of perspectives.

The enormous power of media in shaping our collective response to the pandemic is clear from both of these sources. It’s not just about reporting facts; it’s also about creating a story. And this narrative has real consequences, ranging from how we act in a health crisis to how we support or oppose public health measures.

This revelation calls for sharper attention and curiosity. It’s about understanding the reasons behind the stories we hear. As we sift through this deluge of information, honing our media literacy becomes essential. It’s important to be on guard, to ask questions, and to understand that the narrator’s perspective shapes every headline and story.

In essence, the discourse on social media isn’t just chatter; it forms the backbone of our public conversations. Engaging with it critically is not just for scholars; it’s our responsibility as informed citizens.

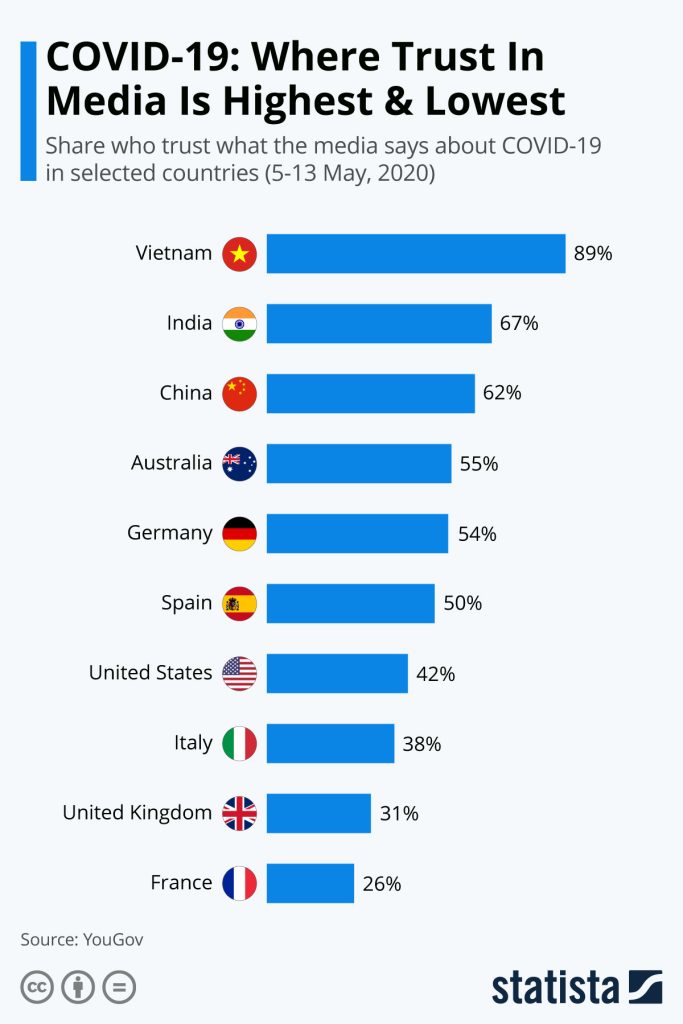

Additional Info: Media Framing of COVID-19 Globally

- Explore how different countries report on COVID-19 in this Boston University article. It’s a concise yet enlightening read on the varied media narratives across the globe.

- Berkeley Conversations

Reference list

Eckart, K. (2022). How Black Lives Matter protests sparked interest, can lead to change. UW News. Available from https://www.washington.edu/news/2022/03/07/how-black-lives-matter-protests-sparked-interest-can-lead-to-change/#:~:text=URL%3A%20https%3A%2F%2Fwww.washington.edu%2Fnews%2F2022%2F03%2F07%2Fhow [Accessed 4 December 2023].

Howarth, D.R. (2000). Discourse. Buckingham England ; Philadelphia, Pa: Open University Press.

Price, S. and Harbisher, B. (2021). Power, Media and the Covid-19 Pandemic. London: Routledge. Available from https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003147299.

Said, E.W. (1997). Covering Islam : how the media and the experts determine how we see the rest of the world. New York: Vintage Books.

Wallace, R. (2018). How the news media framed the Syrian refugee crisis. Policy Options. Available from https://policyoptions.irpp.org/magazines/march-2018/how-the-news-media-framed-the-syrian-refugee-crisis/#:~:text=URL%3A%20https%3A%2F%2Fpolicyoptions.irpp.org%2Fmagazines%2Fmarch [Accessed 3 December 2023].

Wicke, P. and Bolognesi, M.M. (2020). Framing COVID-19: How we conceptualize and discuss the pandemic on Twitter. PLOS ONE, 15 (9), e0240010. Available from https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0240010 [Accessed 3 December 2023].

Hello! Your article uses a great example – Covid 19 – to validate the points made – demonstrating the power of discourse through how it affects people’s perceptions of the epidemic on Twitter. But it also shows just as well that discourse can be controlled by some powerful organ or figure.It’s great.Great article.Great article!

The article explains the meaning of the first sentence to the reader with a very direct example at the beginning. And the same strategy is used throughout the blog.This blog uses a large number of examples (events, articles and books) to demonstrate the central point, which is “It’s not always about the truth, but what they want us to believe or feel.”