In a world saturated with information, the concept of “manufacturing consent” has become a critical lens through which we can understand the dynamics of media, politics, and societal narratives. Coined by political scientists Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky in their influential work, “Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media,” the term refers to the subtle, often unnoticed mechanisms through which powerful entities shape public opinion. In this blog post, we will explore the multifaceted nature of manufacturing consent and its implications for our understanding of information dissemination.

The Propaganda Model:

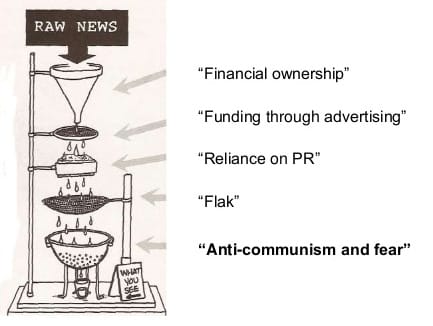

Herman and Chomsky’s Propaganda Model outlines five filters that shape the information we receive: ownership, advertising, sourcing, flak, and anti-communism (or more broadly, an establishment-friendly ideology). These filters work together to create a system where certain perspectives are privileged, while others are marginalized or excluded. For instance, media outlets owned by large corporations may be less inclined to publish content that challenges corporate interests, thereby manufacturing consent by limiting the range of acceptable discourse.

The Role of Advertising:

Advertising revenue plays a pivotal role in the media landscape, influencing editorial decisions and content creation. As media outlets rely heavily on advertising to fund their operations, there is an inherent pressure to appeal to advertisers and avoid content that might be deemed controversial. This results in a form of self-censorship where stories that challenge the status quo or powerful interests may be downplayed or neglected, effectively shaping public opinion through the content that is presented to the audience.

Sourcing and Access:

The choice of sources in news reporting is another crucial aspect of manufacturing consent. Journalists often rely on official sources, such as government officials or corporate spokespersons, for information. This reliance on established authorities can lead to a distorted narrative that aligns with the interests of those in power. Meanwhile, alternative voices and grassroots perspectives may be marginalized, reinforcing the dominant narrative and limiting the diversity of opinions available to the public.

Flak and Consequences:

Flak refers to the negative responses and criticism that media outlets may face when they deviate from the accepted narrative. Individuals or organizations with significant power and resources can exert pressure on media through legal threats, public relations campaigns, or other means. The fear of facing flak often results in self-censorship, with media outlets opting for a more cautious approach to avoid backlash. This process further solidifies the manufactured consent by discouraging dissenting voices and reinforcing the existing power structures.

Conclusion:

Understanding the concept of manufacturing consent is essential for navigating the complex landscape of information dissemination. As consumers of information, we must be critical of the sources we rely on, recognizing the influence of various filters that shape the narratives presented to us. By fostering media literacy and supporting diverse voices, we can actively challenge the manufactured consent and strive for a more pluralistic and democratic exchange of ideas. In a world where information is power, being aware of the subtle mechanisms at play is a crucial step towards fostering a more informed and empowered society.

References:

A Propaganda Model, by Noam Chomsky (Excerpted from Manufacturing Consent)

Manufacturing Consent: Noam Chomsky on Politics & Media (thecollector.com)