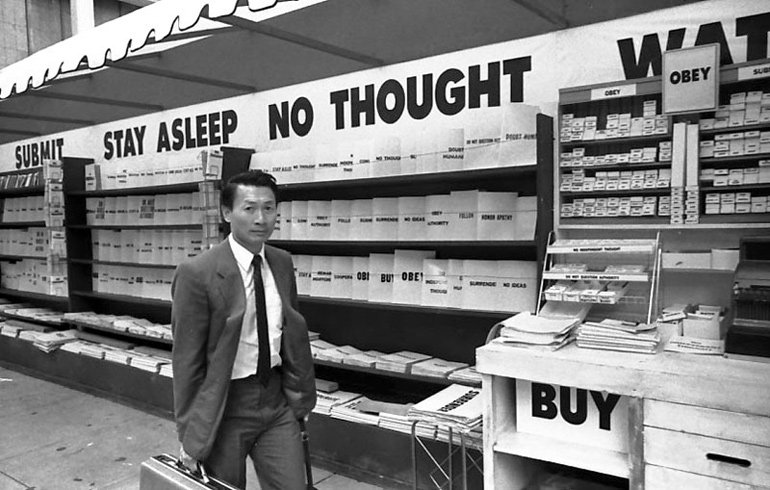

The culture industry, a term coined by Theodore Adorno and Max Horkheimer, critiques how mass-produced culture manipulates society, creating passive consumers and standardising cultural experiences.

They first introduced this in their 1947 book “Dialect of Enlightenment”, more specifically, the chapter titled “The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception”. Adorno and Horkheimer stated that cultural products are manufactured to be uniform, which diminishes individuality and creativity. This standardisation leads to a homogenised culture where diverse expressions are replaced by formulaic content designed to maximise profit; most cultural products follow the same formula or pattern (e.g. predictable movie plots, pop songs with similar structures etc). In the culture industry, conformity is enforced through culture as a tool to control the masses, and keep society distracted from the problems of class conflict and inequality.

They argued that the culture industry creates false psychological needs that can only be satisfied by it’s products. This results in a society that is distracted from their genuine needs for freedom, creativity, and individuality, ultimately reinforcing the status quo of capitalism. They outline how the culture industry has created a passive consumer, whose uncritical thinking contributes to their own oppression.

While Adorno and Horkheimer’s analysis has been widely influential, it has also faced criticism for its lack of empirical evidence. It has been argued that their generalisation of all cultural products being oppressive overlooks the potential for resistance from the masses. However, despite these critiques, the general concept of culture industry remains heavily relevant in today’s world of social media. Platforms such as Netflix, TikTok and Spotify are all victims of the culture industry; mass producing culture for profit while using algorithmic recommendations.

More recent studies by media theorist David Hesmondalgh (2002) state that companies need to ‘minimise risk and maximise profit’ to be successful, falling directly in line with the work of Adorno and Horkheimer. While Adorno and Horkheimer saw culture as a system of mass deception, Hesmondalgh argues it’s more nuanced, stating there are multiple different industries, with varying degrees of creativity, control, and resistance – for example, music, film, gaming etc.

Similarly, Henry Jenkins (2006) explores the idea of “participatory culture” in his book Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide (2006). Where Adorno and Horkheimer saw mass deception as passivity, Jenkins sees participation, creativity and collaboration between producers and consumers. Jenkins doesn’t deny corporate control, he argues that participation and exploitation co-exist.

In conclusion, the culture industry is as relevant today as it was when Adorno and Horkheimer first coined the term; even more so living in a day and age where the media surrounds us and social media has taken over a huge chunk of the general populations daily lives.

References:

Hesmondhalgh, D. (2019). The Cultural Industries (4th ed.). London: SAGE Publications. (Accessed 20/10/2025).

Jenkins, H. (2008). “Convergence Culture.” In The International Encyclopedia of Communication. Oxford: Blackwell. (Accessed 20/10/2025).

Adorno, T. W., & Horkheimer, M. (2002 [1944]). Dialectic of Enlightenment: Philosophical Fragments. (E. Jephcott, Trans.). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. (Accessed 20/10/2025). Available at:

HI, your post provides a really clear and well structured explanation of Adorno and Horkheimer’s concept of of colour industry, and i think you did an excellent job connecting their original 1947 work to modern platforms like Netflix, TikTok, and Spotify. I especially liked how it highlighted the shit from “false needs” to algorithmic recommendations today, it shows strong understanding of how their theory pilots in a contemporary context.

You provide a clear and well-organized comparison between the original Frankfurt School idea of the culture industry and today’s media environments. You clearly explain Adorno and Horkheimer’s main points about standardisation, passivity, and the creation of false needs, and you also mention the criticisms of their views. By including Hesmondhalgh and Jenkins, you show how later thinkers add to or challenge the original model, especially with ideas about risk management, creativity, and participatory culture. Your writing shows a strong understanding of both classic and current debates about the culture industry and why it still matters in the age of algorithm-driven media.