The male gaze, first theorised by Laura Mulvey (1975), describes how visual media positions women as objects of heterosexual male desire. While Mulvey was writing about Hollywood cinema, TikTok—with its short-form videos, algorithmic curation, and participatory culture—offers a new arena where the gaze operates in more complex ways. On a platform where visibility is currency, the aesthetics of the male gaze continue to shape what becomes popular, what gets recommended, and even how creators present themselves.

A clear example can be seen in TikTok’s “clean girl,” “that girl,” and “get ready with me” (#GRWM) trends. These videos often centre on women presenting their bodies, routines, or lifestyles through highly aestheticised visuals: smooth skin, carefully styled outfits, soft lighting, and curated femininity. The camera lingers on faces and bodies in a way that echoes the visual tropes Mulvey identified—framing women as objects to be looked at and evaluated. But unlike classical cinema, TikTok creators control the camera. Many intentionally craft themselves through gaze-friendly imagery because they know it appeals to viewers and the algorithm alike.

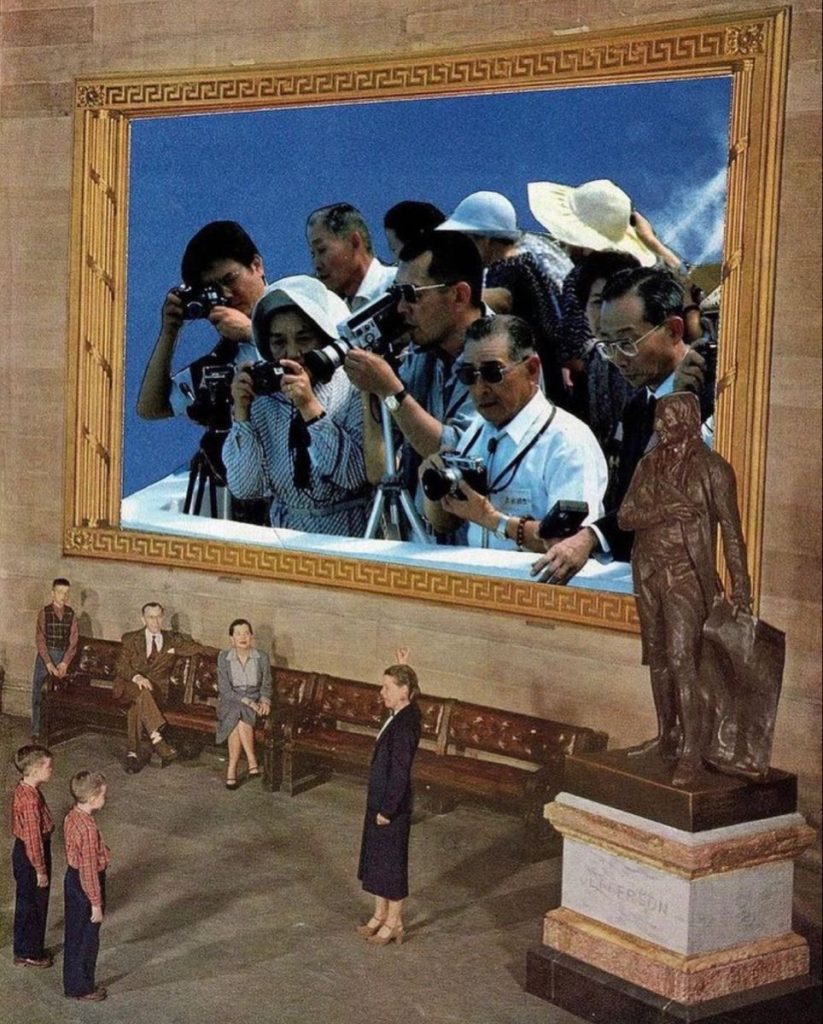

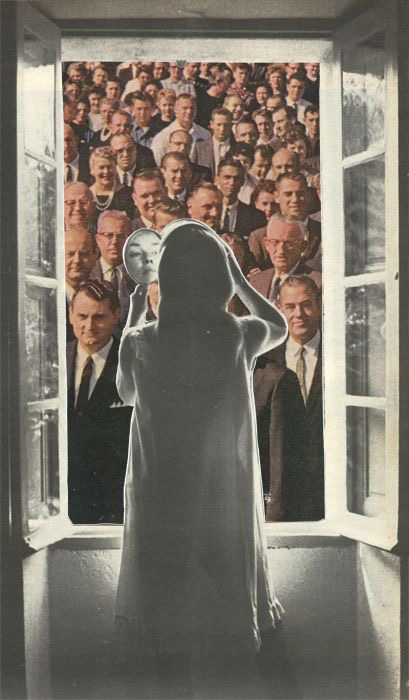

This raises an important question: is TikTok empowering women to control their own representation, or does it encourage them to reproduce an internalised male gaze? Gill (2007) argues that contemporary media culture promotes “self-sexualisation” as a form of empowerment, where women appear to choose visually pleasing self-presentations but still operate within the boundaries of heteronormative beauty standards. On TikTok, this is amplified by the algorithm, which rewards content that fits conventional attractiveness. Even creators not intending to appeal to a heterosexual male audience can end up conforming to gaze-driven aesthetics simply because that is what performs well.

However, TikTok also complicates Mulvey’s theory. The platform is full of creators—women, queer people, and non-binary users—who actively subvert the male gaze. Body-positivity creators reject polished, sexualised aesthetics in favour of authenticity. Others parody influencer beauty routines or exaggerate stereotypical “sexy poses” to critique how social media conditions people to display themselves. These forms of resistance show that users are not simply passive subjects of the gaze, but active participants who negotiate, challenge, or even mock it.

Reflecting on my own TikTok use, I notice how subtly the logic of the gaze influences everyday posting. When recording videos, I sometimes adjust the camera angle, fix my lighting, or retake a clip if I feel I don’t “look right.” Even without thinking about it, I am responding to what I believe audiences expect to see on TikTok. Mulvey’s theory helps me recognise how deeply embedded these visual norms are, but it doesn’t capture the full complexity of a platform where the gaze is not only male but also algorithmic, communal, and self-directed.

Ultimately, TikTok shows that the male gaze has not disappeared—it has multiplied. The platform blends self-presentation, performance, and algorithmic visibility in ways that encourage both conformity and creativity. Understanding the male gaze today means recognising how it shapes digital aesthetics while also paying attention to the many users who push back, remix, and redefine what it means to be seen.

References

Gill, R. (2007) Gender and the Media. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Mulvey, L. (1975) ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’, Screen, 16(3), pp. 6–18.