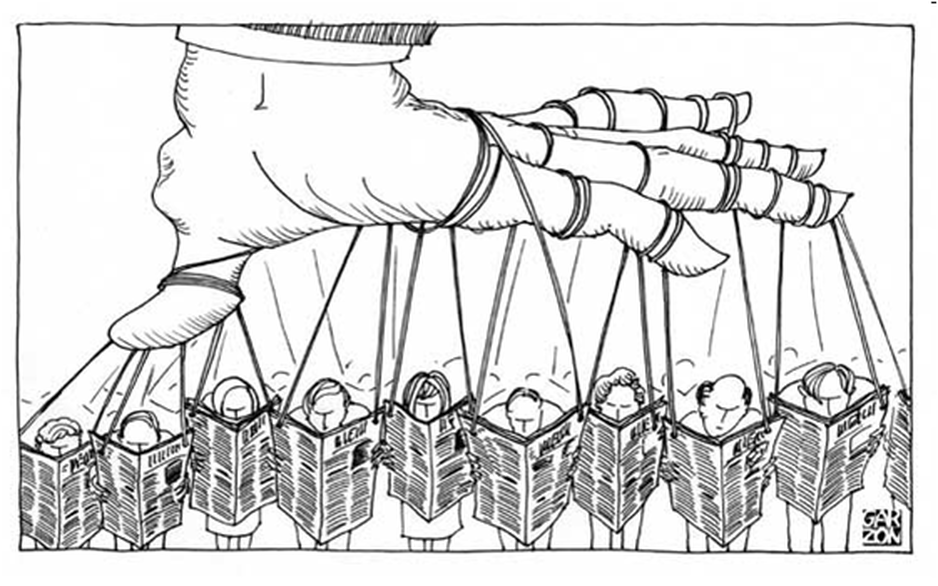

When people hear the phrase “manufacturing consent,” it sounds dramatic, almost like something out of a dystopian film. But the idea is actually much more subtle. It comes from Edward Herman and Noam Chomsky, who argue that the mass media don’t simply report news. It also shapes how we think about political events, what we pay attention to, and what we ignore. Most of the time, this happens quietly, without us really noticing (Herman and Chomsky, 2008).

Herman and Chomsky describe something called the propaganda model. This doesn’t mean all journalists are lying or secretly working for the government. Instead, it means the way the media system is structured (who owns it, how it is funded, how news is selected, and who gets quoted) naturally produces a certain view of the world. That view often lines up with the interests of powerful political and economic groups.

Their model is built around a set of filters. These filters shape what becomes news and how it is framed. Ownership is a major one. Most big media organisations are owned by large corporations that have their own financial and political interests. That can affect which stories are emphasised and which ones are downplayed. Advertising is another filter. Because media outlets depend on advertisers for money, they are less likely to promote content that might scare advertisers away.

Another key filter is sourcing. Herman and Chomsky point out that journalists rely heavily on official sources, like government officials, police, big companies, and established experts. These sources are easy to access and seen as credible, but this also means that alternative voices and critical perspectives are often pushed to the margins. Over time, this creates a situation where some opinions sound “normal” or “common sense,” while others barely appear in mainstream coverage at all.

This theory feels especially relevant today. We see it in the way some international conflicts dominate headlines, while others are barely mentioned. We see it in how political issues are simplified into two sides, even when the reality is much more complicated. We also see it in how stories are packaged to be attention-grabbing, fast, and easy to consume rather than deep or challenging.

Social media has changed the landscape but hasn’t removed the problem. On one hand, more people can share information and challenge official narratives. On the other hand, algorithms promote content that gets the most engagement, not necessarily what is most accurate or important. That means certain narratives can still be pushed to the front, while others get buried.

The point of manufacturing consent is not to say that all media is fake or evil. It is more about encouraging us to be aware of the systems behind what we see. Once we understand that news goes through these filters, we can start asking better questions: Why is this story being told in this way? What is missing? Who benefits from this version of events?

In the end, the concept of manufacturing consent is a reminder to stay critical and active as media users, rather than just accepting everything at face value.

Reference:

- Herman, E.S. and Chomsky, N. (2008) Manufacturing consent: the political economy of the mass media. Anniversary edition / with a new afterword by Edward S. Herman. London: Bodley Head. Available at: http://www.vlebooks.com/vleweb/product/openreader?id=WestminUni&isbn=9781407054056

Recent Comments