Ever wondered why two people can watch the same TikTok or read the same tweet and take completely different things from it? The answer lies in Stuart Hall’s theory of encoding and decoding a framework that’s still essential for understanding how contemporary media and communication work. This blog explores how these ideas play out in the content we consume every day, from social media trends to advertising.

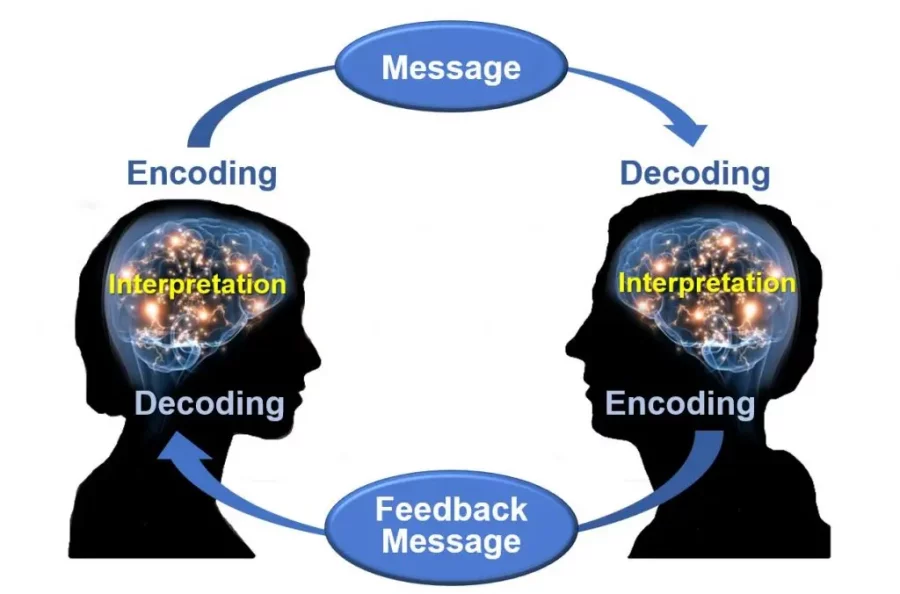

Encoding: How media makers put their message out there

Encoding is determined by the choices made during the media creation process regarding visual material, language, narrative and tone. This affects the audience’s preferred reading. By releasing behind the scenes photos, speaking informally, or collaborating with influencers who represent the preferences and way of life of their target audience, brands on Instagram, for instance, frequently express relatability and authenticity. Such choices are made in order to create a current perception: that the brand is reliable, consistent with the consumer’s values, and a part of their daily existence. However, those encoded intentions don’t always resonate because digital platforms distribute content to a wide range of audiences.

The shift from standard broadcasting to algorithm-driven distribution is making it more difficult for meanings to spread.

Decoding: How we make sense of what we see

The twist is that the encoded message is rather than just quietly received by people. Decoding is the interpretation that we, as viewers, assign to or develop in light of our experiences, values, culture, or beliefs. Hall identified three main ways that humans interpret media:

Dominant-hegemonic position: The audience unquestioningly takes the encoded message as it is intended. The Coca-Cola ad would sound, to those who come across it, like, “Wow, this shows how we can all come together.”

Negotiated position: The audience takes part of the message but questions the other. For instance, “I like the idea of unity, but Coca-Cola is a giant company that may not live up to what it preaches.”

Oppositional position: The audience completely rejects the encoded message. One could say, “This is just a cynical gimmick to sell more soda by leveraging social justice trends.”

A contemporary analogue is the #BlackLivesMatter hashtag. Media outlets have coded it as a racial equality movement, but audiences interpret it differently: it’s embraced fully, negotiated by some who endorse the cause but criticise specific acts, and opposed outright by a small minority.

From watching to remixing

One of the major advancements brought out by digital media is moving from a passive audience to an active audience. Through stitches, duets, memes, remixes, and reposts, not only do they decode messages, but also re-encode, making meaning. One reel or TikTok may contain in it just one message, perhaps encoded, but in the face of such multiple meanings and all content for another, go viral in another way each audience is reinterpreting, parodying, or changing it, in a playful or oppositional way. The participatory culture described by Jenkins (2006), corroborates Hall’s argument that audiences actively construct media meaning a process in turn expedited by algorithms, which feed information to personalised feeds and produce more diverse readings.

Conclusion

To fully understand how meaning is created, perceived, and challenged in modern media, Hall’s encoding and decoding approach is still crucial. The theory emphasises the dynamic interaction between producers and viewers and enables us to consider the complexity of contemporary communication, whether we are examining political memes, influencer advertising, or TikTok trends.

References

Hall, S. (1980). ‘Encoding/decoding’. In Culture, Media, Language. London: Hutchinson.

Jenkins, H. (2006). Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. NYU Press.