Goffman used theatrical concepts to explain everyday life, employing a theatrical metaphor as the framework for his theory. In his theory of self-presentation, Goffman introduced the concepts of “front stage” and “back stage” to explain the different ways people behave in social interactions. The front stage is the “stage” where individuals present their identities to others. Here, people generally act according to societal expectations and roles, displaying behavior appropriate to the occasion. In contrast, the back stage is a “private space” where individuals can let down their guard and show their true selves. In the back stage, people no longer need to conform to external expectations and can act more relaxed and naturally. Without a front stage, social order would be compromised; however, without a back stage, life would become too burdensome.

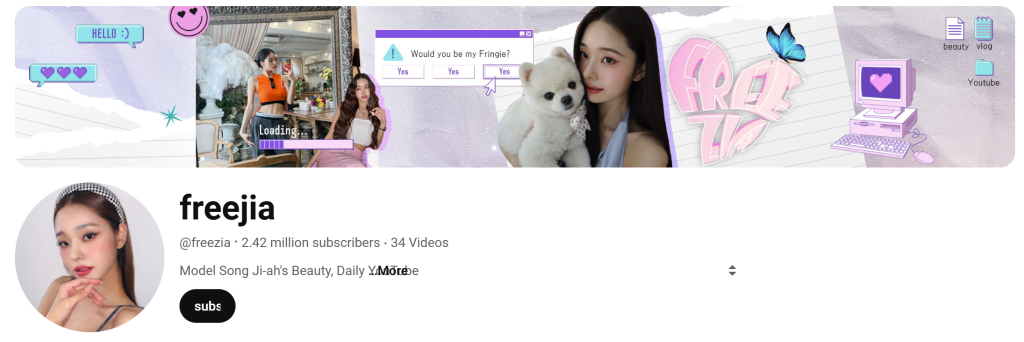

Song Ji-a quickly rose to fame after participating in the popular Korean reality show Single’s Inferno. Her sophisticated and fashionable image on the show attracted widespread attention. Users have increasingly started to indulge in a culture of looking ‘attractive’ to get more ‘likes’. Her high-end lifestyle, luxurious outfits, and stylish taste sparked viewers’ fascination with her “wealthy and beautiful” persona, creating a strong front-stage image that attracted a large fanbase. However, this identity was not entirely authentic but rather a carefully curated and crafted image. Before long, netizens discovered that many of the luxury items she showcased were actually counterfeit.

The incident began when observant fans noticed flaws in the luxury items Song Ji-a showcased on social media, such as branded clothing, bags, and accessories from Chanel, Dior, and other high-end brands. After careful comparison, they found that these items did not fully match the official designs, with some even showing significant differences in detail. This sparked widespread discussion, with many netizens questioning whether she had used counterfeit goods to create a fake “wealthy and beautiful” image, thereby deceiving her audience for attention and trust.

In response to the criticism, Song Ji-a posted an apology on social media, admitting to using fake luxury items and expressing regret, explaining that it was her “vanity” that led her to make such choices. She added, “At first, I only bought them because they were pretty, but as my popularity grew, it seems I lost myself.” She deleted the photos featuring counterfeit items and temporarily halted updates on her social media platforms. Despite her apology, the incident dealt a heavy blow to her image and influencer career. Fans and viewers started to seriously question her authenticity, and several brand partnerships were affected as a result.

This “counterfeit incident” reveals the potentially deceptive methods influencers may adopt in constructing their identities, such as presenting a fake luxury lifestyle to attract attention. While this approach may yield short-term success, once the truth is exposed, it can have lasting negative impacts on the individual’s credibility and public image.

When we play our roles, we present a series of masks to others, carefully controlling and arranging our image, always concerned with the impression we leave. We constantly strive to position ourselves in the most favorable light, aiming to present our best possible self (Goffman, 2002). Song Ji-a’s incident not only exposes the trend of individuals on social media creating false images in pursuit of fame and wealth but also highlights the authenticity crisis prevalent in the influencer economy. Goffman’s theory of identity construction reminds us that when a “front-stage” image is built on deception and over-packaging, an individual, once exposed, faces a significant trust crisis and moral scrutiny. Song Ji-a’s example underscores the tolerance for inauthentic identities within the influencer industry, leading many to prioritize excessive front-stage performances over authenticity. This incident serves as a reminder that in an era dominated by influencer culture and consumerism, we must approach the so-called “perfect image” with greater rationality and reconsider the value of an authentic self in the digital age.

Reference

Goffman, E., 2002. The presentation of self in everyday life. 1959. Garden City, NY, 259.

Haziq, S. (2019) “Putting the best digital self forward in the age of Social Media”, Medium. Available at: https://medium.com/@haziqsabreen25/putting-the-best-digital-self-forward-in-the-age-of-social-media-d3dbec422b73 (Last accessed: 02.11.2024)

In my opinion, the front stage image of the network celebrity mentioned by the blogger and presented to the public is indeed a very prominent problem in today’s society and the Internet society, because the network celebrity obtains benefits for themselves through the front stage image. In addition to what the blogger mentioned, in recent years, there are many Internet celebrities who choose to live broadcast their goods, and many of the goods they sell do not meet the basic standards, such as China’s tens of millions of Internet celebrities, Xiao Yang ge and Dongbei yu jie. Some of the products they sell do not meet the standards, but the fan groups and audiences yearn for and love their front stage image. And buy their goods. So when their front stage image collapses, or someone points out that something is wrong with what they are selling, they are subject to more anger and criticism. Therefore, I think in addition to the network celebrities need to cherish and care for their own front stage images, the audience and fans should also have more rationality to look at the front images carefully packaged in this Internet era, so as to better improve their own judgment and judgment ability to protect themselves.

Your blog cleverly combines Goffman’s theory of drama with an in-depth look at Song Zhiya’s case to reveal the complexity and potential problems of identity construction in the age of social media. I also followed this variety show before, knowing that at that time she caused a lot of discussion and pursuit, and then the collapse of the people is also surprising. Many such cases happen around us all the time. In fact, we can further explore how to balance authenticity and social media presence. But overall I find your blog very interesting and the case is very clear and specific.