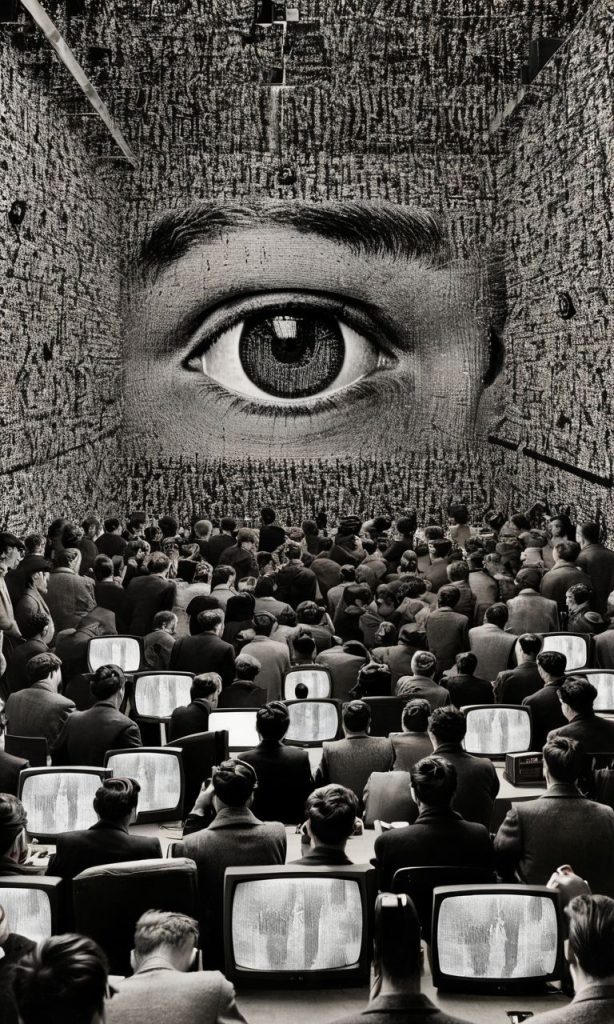

The term “culture industry” was coined by Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer in Dialectic of Enlightenment (1944). They argued that under capitalism, culture ceases to be an expression of creativity and becomes a mass-produced commodity, designed to generate profit and maintain social control. Art, once a form of resistance and reflection, becomes standardized, predictable, and safe — ensuring the audience remains passive consumers rather than active critics.

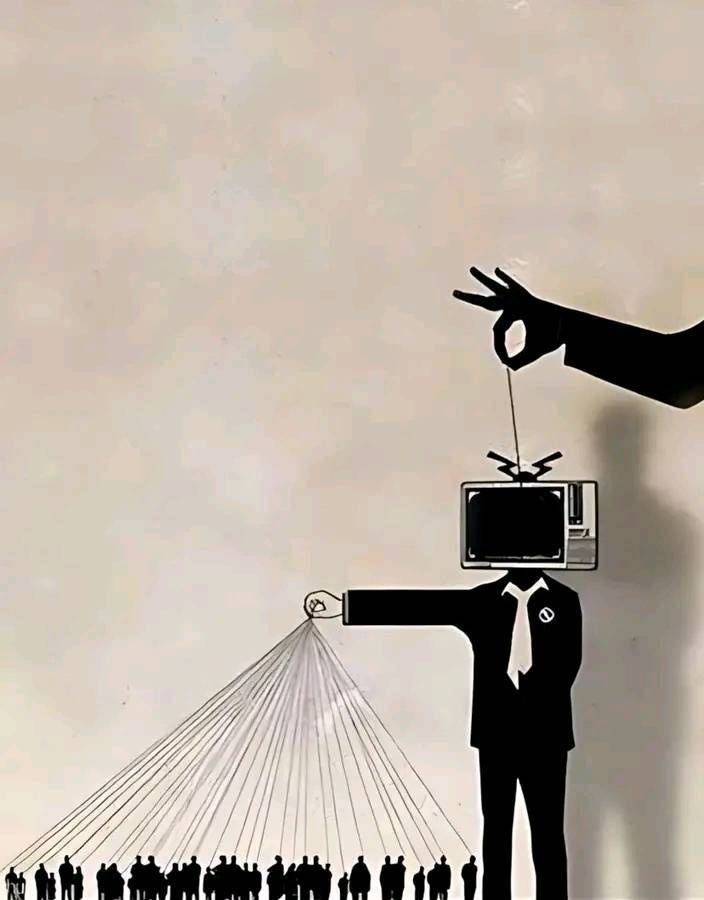

Today, this concept feels eerily familiar. Our streaming playlists, TikTok feeds, and Netflix recommendations all follow the same industrial logic: produce what sells, not what challenges. As Adorno and Horkheimer warned, entertainment becomes a tool of conformity disguised as choice.

If Adorno lived in the age of Spotify algorithms and Netflix AI, he might have said, “The algorithm is the new assembly line.”

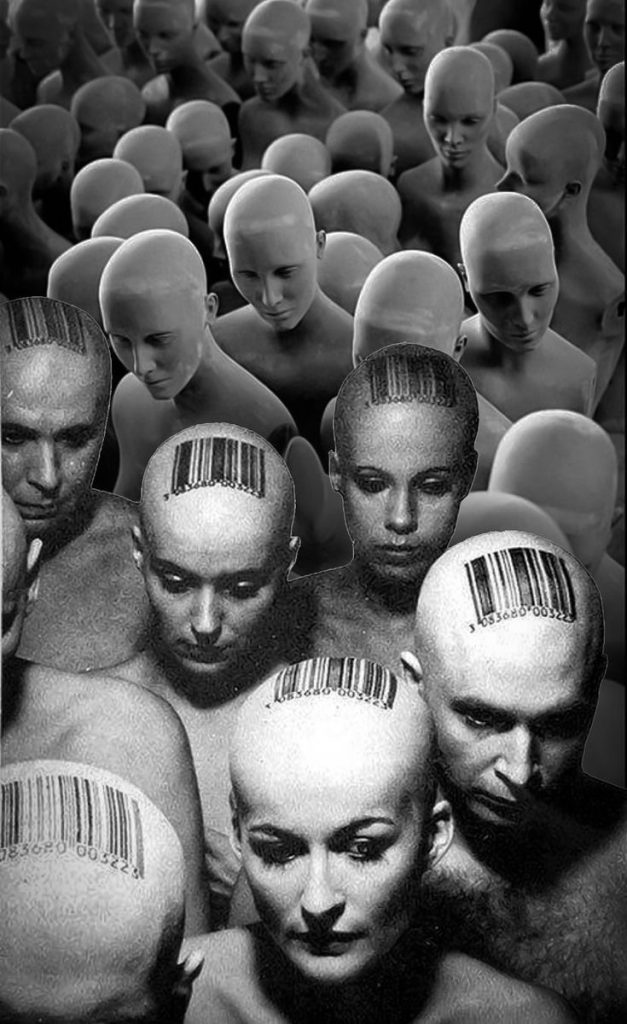

In the 1940s, the culture industry was powered by Hollywood studios and record labels. Today, it’s powered by data analytics and algorithmic curation. Instead of marketing executives predicting trends, machines analyze user behavior and reproduce what performs well — often amplifying the familiar, the formulaic, the clickable.

But there’s a paradox. While digital culture offers unprecedented access and personalization, it also deepens standardization. The same few pop songs dominate global charts. Netflix Originals follow eerily similar structures. Even online “authenticity” becomes commodified — influencers sell relatability as a brand.

Thus, the illusion of choice that Adorno and Horkheimer critiqued has only become more sophisticated. We scroll endlessly, believing we’re choosing freely, when in fact we’re being guided — subtly, invisibly — by systems that optimize engagement and profit.

Reflecting on my own media habits, I realize how complicit I am in this system. I let Spotify’s “Discover Weekly” choose my new music, assuming it “knows” my taste better than I do. I binge-watch trending series on Netflix, drawn in by the buzz rather than the content’s depth.

Yet, this reflection also reveals a tension: pleasure and critique coexist. As cultural theorist John Storey (2015) notes, popular culture can’t be dismissed as mere manipulation; it’s also a space where meaning, resistance, and identity are negotiated.

When I listen to K-pop or watch Marvel movies, I’m both consuming and interpreting — finding emotional resonance even within corporate production. This complexity shows that while Adorno’s critique remains valid, the culture industry also enables new forms of participation, fandom, and creativity.

In addition to Adorno & Horkheimer’s foundational theory, more recent thinkers like David Hesmondhalgh (2019) in The Cultural Industries argue that cultural production is not purely manipulative but shaped by tensions between creativity, commerce, and regulation.

Similarly, Henry Jenkins (2006) in Convergence Culture explores how audiences have become more active, engaging in remixing, fan fiction, and participatory media — practices that both challenge and reinforce capitalist structures.

These perspectives suggest that the “culture industry” is no longer a one-way system of domination but a dynamic field of negotiation between producers, platforms, and audiences.

The culture industry remains one of the most powerful frameworks for understanding how capitalism colonizes culture, but we must reinterpret it in light of digital capitalism. The industrial logic of standardization persists, but now it operates through data-driven personalization.

The originality of our era lies in this contradiction: culture feels more individualized than ever, yet is governed by algorithmic sameness. We are not only consumers of culture — we are its raw material. Our clicks, likes, and watch times are the new labor that fuels the system.

The culture industry is no longer a factory churning out films and records; it’s a networked ecosystem where culture is constantly produced, circulated, and monetized.

To break free — or at least become conscious participants — we must reclaim our role as critical consumers:

As Adorno once warned, “Amusement under late capitalism is the prolongation of work.”

Perhaps the true act of rebellion is to pause, reflect, and ask — who benefits from my attention?

The culture industry is not a relic of the past but a living system that evolves with technology. Its critique still matters — not as a rejection of pleasure, but as a call for critical awareness.

If culture has become industrialized, then reflection itself is our last act of resistance.

References

Adorno, T., & Horkheimer, M. (1944). Available at: Dialectic of Enlightenment.(Accessed 20 October 2025)

Hesmondhalgh, D. (2019). Available at: The Cultural Industries (4th ed.). SAGE. (Accessed 20 October 2025)

Jenkins, H. (2006). Available at: Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York University Press. (Accessed 20 October 2025)

Srnicek, N. (2017). Available at: Platform Capitalism. Polity Press. (Accessed 20 October 2025)

Storey, J. (2015). Available at: Cultural Theory and Popular Culture. Routledge. (Accessed 20 October 2025)

Van Dijck, J. (2013). Available at: The Culture of Connectivity: A Critical History of Social Media. Oxford University Press. (Accessed 20 October 2025)

Zuboff, S. (2019). Available at: The Age of Surveillance Capitalism. Profile Books. (Accessed 20 October 2025)

This is such a thoughtful post; you explain Adorno and Horkheimer’s idea in a way that really connects to how we experience media today. You explain in such a clear way how personalization can actually lead to sameness. I like how you added hands on advice.

I also like how you bring in Jenkins and Hesmondhalgh to balance things out — it’s true that while culture is shaped by profit and data, people still find ways to be creative and make meaning.

That last line about reflection being an act of resistance is powerful. It’s a great reminder that being aware of how and why we consume media is already a step toward thinking more critically.